There’s been a lot of buzz around since the subject matter of Christopher Nolan’s next major film was announced as Homer’s Odyssey, and an equally large amount of discourse. It has been interesting to see how, to some, it is a central piece of literature that every person should read about, and to many it was required reading in schools. To others it is unfamiliar and equally inaccessible. I can certainly imagine that a few people have picked up a copy, lasted a few pages of Telemachus shenanigans and thought… what the hell? Which is a fair response to encountering Epic for the first time.

As someone who has taught the text to students new to the classical world and classical literature, it’s a tricky process to first access the work but once achieved it can be quite rewarding. So I thought I’d start with a beginner’s guide to the text and, if readers are keen, I can write some more detailed analyses.

What is the Odyssey?

The first thing I tell anyone new to the Odyssey is that it is not a novel. In fact it predates the concept of a novel by millennia! Rather it a piece of Epic Poetry, which differs in many significant ways. Let’s look at some of the key features of Epic:

It began from the concept of oral storytelling - imagine the type of stories told around the campfire - and over time, story tellers got better and better at their craft until it became its own stylised genre.

As a result, it was not written down and recited - every performance was live and unique. You could see the same work done completely differently on two different occasions.

Many of the tropes and stylistic features of epic developed because it was delivered in this way - type scenes, epithets, extended similes and more.

Importantly, it was a type of poetry (which doesn’t mean it rhymed) but it had a meter, which would give a constant rhythm to the recitation. Many are familiar with iambic pentameter, the relatively easy meter of Shakespeare’s verse.

The meter of Homer was dactylic hexameter, which is more complex and difficult to fit words into, meaning that it took a great deal of skill to be able to compose these Epics off the cuff.

What we know as the Odyssey is the culmination of many centuries of this craft and in a more formalised version of this style. It would have begun life as a simple story that got added to and extended over many iterations. By the time that someone decided to write it down, it may have reached a more fixed version or simply this is just the one version that someone happened to hear. Which then leads to the question…

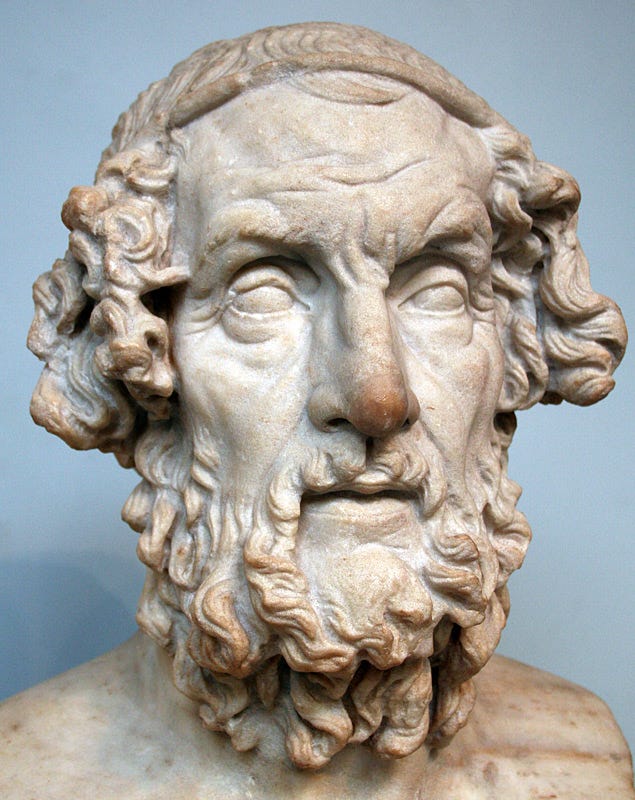

Who was Homer?

Short answer? We don’t know. Maybe no one. Maybe someone but necessarily the author of this work. As said above, the process of oral storytelling was one that developed over a long period of time. These story-tellers, or bards, passed on their skill from one generation to the next and with them each story gained a new life. Homer may well have been a bard early in this process, whose skill and craft meant that his name became attached to the story. Or he may have been a persona invented to give a more mystical quality to the origins. Or he may have been the last person to recite it before someone wrote it down.

One way or another, Homer is essentially as mythical as the characters in his works, but we have no better choice to put down as the author, so it has stuck! The mythical qualities ascribed to him include that he was an old, blind man who lived in Anatolia where the Ionian Greeks settled. This meant he was Greek but also intimately familiar with the world of the mythical Trojans in modern Turkey. His lifetime is placed around the 8th or 7th century BC, which was likely when the oral tradition really kicked off.

How do I read the Odyssey?

Keeping in mind what I said above, there are a couple of things to do before you pick up a copy of the work and begin reading. Here are my key pieces of advice:

Pick a translation that suits you - decide if you want one that sounds old-fashioned and serious, modern and accessible, or lyrical and poetic. There are plenty of choices for each - try to avoid anything over 100 years old though!

Know the context of the work - the Greeks knew the whole story and surrounding mythology when hearing Epic, there was no concept of spoilers back then! So read up on the Trojan War and the events leading up to - it’s a fun time!

Read up on the structure of the story - you don’t have to read the whole thing, there are definitely some parts you can skip or read a summary for. It will help you get to the more exciting bits!

Not sure about a reference? Google it! There are plenty of asides, throwbacks and name drops throughout the work so definitely check up on who they’re talking about. It probably pays to have a list of secondary characters for reference too.

Other than that, just have fun and read as much as you like!

How is the Odyssey Structured?

Given the oral nature of Epic, the plot structure can be quite complicated. In many cases, it can be seen where various episodes have been inserted into the story to add more to the story. The story starts near the end, ten years having passed since Odysseus left Troy. The story of his return home is mostly told in the middle as Odysseus recounts the journey himself. The second half deals mostly with his homecoming.

If you pick up the book, you will find it divided into 24 chapters (known as books in poetry) and they are structured in the following way:

Books 1-4: These are something of a prologue to the story, and not the most exciting because Odysseus doesn’t even appear! The focus here is on Telemachus, Odysseus’ son, and what has been going on back home while Odysseus was away. It’s useful for establishing that situation and introducing some key themes. It also helps to catch up on what has happened to the other Greeks from the Trojan War, as Telemachus visits Nestor and Menelaus, who fill him in. When teaching this, I will often read Book 1 and skip ahead.

Books 5-8: The action finally shifts to Odysseus, who is imprisoned by Calypso. With some divine intervention, he is allowed to sail off, only to be shipwrecked by Poseidon and wash up in the land of the Phaeacians. There he is rescued and treated well by his hosts, to whom he tells the story of his travels.

Books 9-12: These are the ones most people think of when they think of the Odyssey. In his recounting of his ‘adventures’, Odysseus recalls meeting the Lotus Eaters, the Cyclops, Aeolus, Circe, Scylla and Charybdis, and even venturing to the Underworld. This is definitely the part you should read!

Books 13-20: Odysseus returns home and there is a long, slow build up to his actual return. With help from Athena, he is disguised as a beggar and begins to suss out the situation in his palace. He reveals himself to Telemachus and the maid Eurycleia, but he is abused by the men living in his house - the suitors trying to marry Penelope. The action finally builds up to a dramatic confrontation.

Books 21-22: Penelope hosts a competition to string Odysseus’ bow, but they all fail. Odysseus himself does it easily, and quickly begins to murder them all. There is a long bloody battle in which vengeance is paid out on these wicked men, and the servants that helped them.

Books 23-24: Penelope and Odysseus are reunited - but not before she tests him to make sure it is really her husband. When finally convinced, they spend a blissful night together. Though the story might end there, there is a little epilogue where the families of all the slain suitors come to start another fight - but Athena puts an end to it quickly and wraps up the whole story.

So the story is really in two parts - the events at home in Ithaca, and the events on Odysseus’ travels. The more notable action, with the monsters and adventures, happens in the middle - so for some, they may never make it there! Feel free to skip ahead and read those bits, and maybe go back and read more if you like it!

What are the Main Themes?

One final point to make is that, although the work preceded modern literature, it is still jam-packed with as many themes and ideas as a modern novel. Below are a couple of the main themes to look out for when reading through the story:

Xenia: Far and way the most important theme of this work, which underpins almost every interaction between characters. Xenia was the Greek concept of hospitality or ‘guest-friendship’, which is a reversal of sorts of modern ideas. In these times, a host was expected to treat a stranger at their door with respect and give them all the comforts of home. From the Suitors to the Cyclops, it is at the heart of every meeting.

Justice: Characters who uphold social rules and norms are generally viewed as the ‘good’ guys, but those who break cultural, social and religious customs are met with swift vengeance. This helps to reaffirm why people should respect these values and fear their gods.

Arete: Odysseus, well known for his cunning and trickery, is the embodiment of arete - the Greek value of personal excellence. It encapsulates all the best parts about him: quick-thinking, clever, witty, silver-tongued, strong, brave and so much more. Despite his many misfortunes, Odysseus is always able to rely on his own character to get out of any situation.

Nostos: More of an over-arching concept, nostos is the idea of ‘homecoming’ from which we get nostalgia. The story is a telling of this idea, which includes not just the journey there but also the ability to re-establish oneself on your return. Just for fun, there’s a little katabasis thrown in too - the descent to the Underworld, which all the cool heroes get to do!

There’s plenty of others to look out for but I will leave them for you to discover. If you have any comments of questions, please feel free to drop them here. If you’d like more analysis, I’m keen to do a more in-depth exploration of the work.

Happy New Year!

Natalie Haynes (ex-stand-up comedian, now stand-up classicist) did a really enjoyable retelling of the Odyssey in 27 minutes, recorded in front of a live audience at the BBC Radio Theatre. No prior knowledge necessary.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001brj5